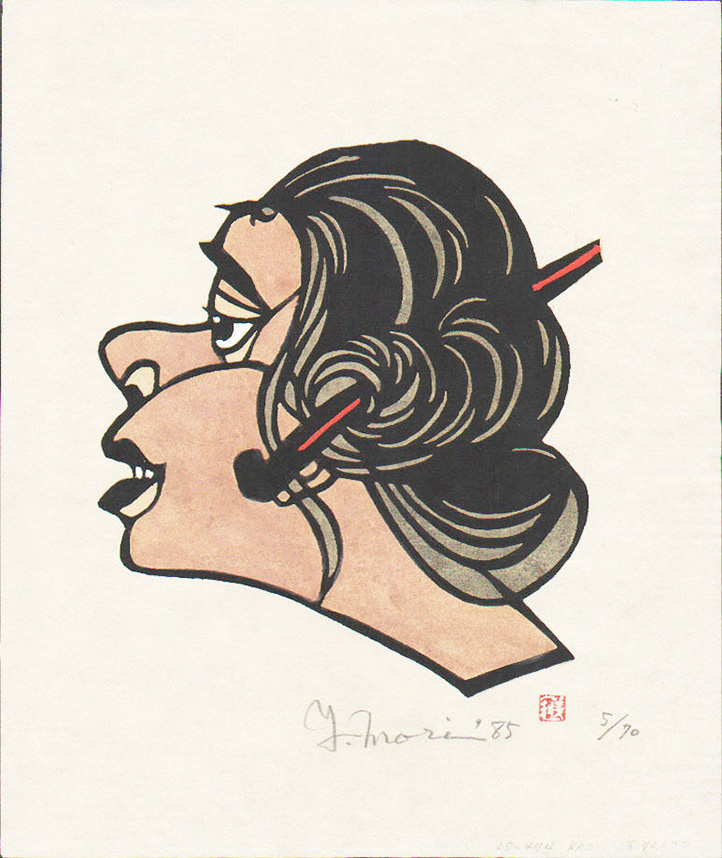

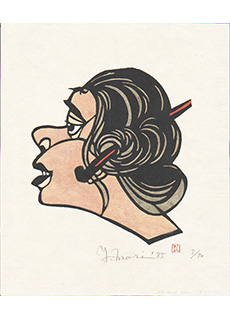

Yoshitoshi Mori (森 義利, Japan, 1898-1992) was a prolific Japanese printmaker and textile dyer who dedicated most of his life to kappazuri stencil printing. He was involved with both the mingei (folk art) and sosaku hanga (creative print) movements. Mori is known for his use of color and depictions of Japanese craftsmen, folklore, and kabuki theater.

Yoshitoshi Mori was born on October 31, 1898 in Nihonbashi, Tokyo, Japan. He was the first-born son of Yonejirō and Mori Yone. Mori’s family was poor and the young artist lived under one roof with all of his extended family. Mori, though, was surrounded by musical family members who played traditional music and nagauta, lyrical songs that originated from kabuki theatre. Music would eventually play a formative artistic and inspirational role in Mori’s life. In his teens, Mori worked odd jobs instead of attending school to help his family. In his spare time, he would sketch and study the illustrated books of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892), Mizuno Toshikata (1866-1908), and Ogata Gekkō (1859-1920). In 1915, at age seventeen, Mori studied kimono dyeing and yūzen (fabric) dyeing with Yamakawa Seihō (dates unknown) and printmaking with Seihō’s son and artist Yamakawa Shūhō (1898-1944). At the age of twenty, Mori was drafted by the army and served two years in Korea.

At the age of twenty-two, Mori entered the Kawabata School of Fine Arts where he worked with textiles and learned the traditional stencil-dyeing technique katazome. This traditional method can be traced back to the Nara period (710-794) and is said to have originated from the Okinawa region. In 1921, Mori entered drawings on silk to the Central Art Exhibition in Tokyo. He also submitted his drawings to the magazine Kōdan Rakugokai and was offered a contract to continue producing designs. However, the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 destroyed the publication firm and Mori was out of work. In 1923, Mori graduated from Kawabata and became a member of Monyō Renmei (Association of Kimono Pattern Craftsmen).

At Kawabata, Mori met artists Serizawa Keisuke (1895-1984, named Living National Treasure in 1956) and Yanagi Sōetsu (1889-1961). Mori also met artists Munakata Shikō (1903-1975) and Sasajima Kihei (1906-1993). The artists contributed to the development of the mingei movement, a Japanese folk art practice of reviving traditional Japanese craft and discovering beauty in ordinary and utilitarian objects during Japan’s rapid modernization and urbanization in the early 20th century. Criteria of mingei arts and craft included representing the region the art was made, was functional, inexpensive, and made by an anonymous craftsperson. In 1954, Mori exhibited his first kappazuri prints at the Nihon Bangain (Japan Woodblock Society).

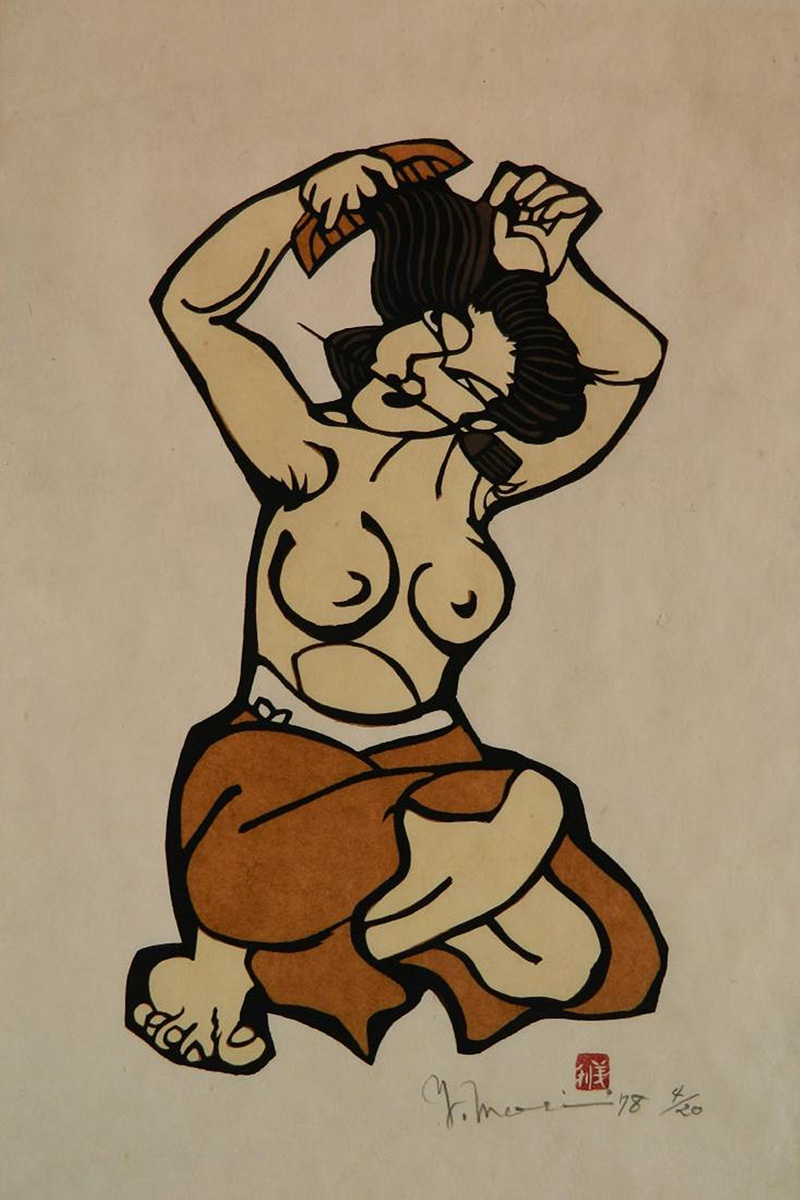

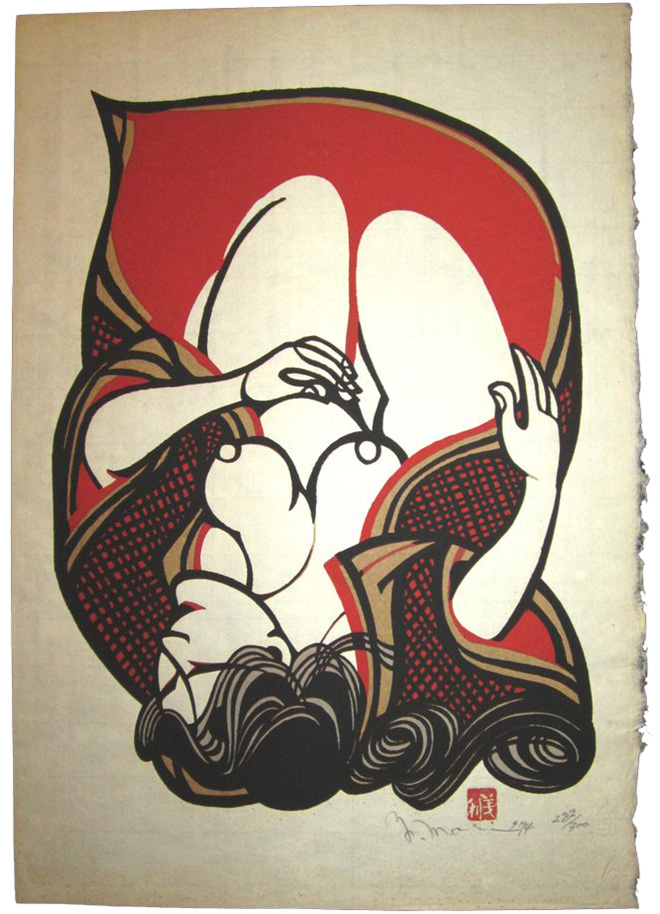

In 1940 and 1941, Mori worked with Watanabe Sadao (1913-1996) under the artist Serizawa Keisuke (1895-1984), a leader in the mingei movement and master of stencil-dyed books who received the Award of Cultural Merit from the Japanese government in 1977. In the 1950s, Mori shifted his focus to works on paper and joined the sōsaku hanga movement. In 1962, his colleague Sōetsu accused Mori of abandoning the mingei movement for the new, modern “creative print” practice that recognized the artist as his own designer and printmaker, similar to how the Western world was introducing artists. However, Mori incorporated his knowledge of dyeing textiles to his printed work. Mori used shibugami paper, which was composed of multiple layers of kozô paper laminated with persimmon tannin. The sheets of paper are dried and smoke-cured to adhere the material. This process makes the paper waterproof, flexible, and strong. The stencil design is created by carving into the paper with a sharp knife, creating the omogata, or equivalent of a woodblock in stencil printing. From the initial design, Mori made several color stencils. Mori reinforced the thin lines with silk gauze and brushed on layers of ink while protecting the white space of the paper with a color-resistant paste called noribuse. After all the color impressions are applied to the paper surface, the key impression is applied. After all ink layers are transmuted to the paper, the print is submerged in water to wash away the paste and hang-dried, a process called mizumoto. Because of the fragility of the stencil prints, as opposed to other printmaking techniques like woodblocks, the number of copies from one set of stencils was limited.

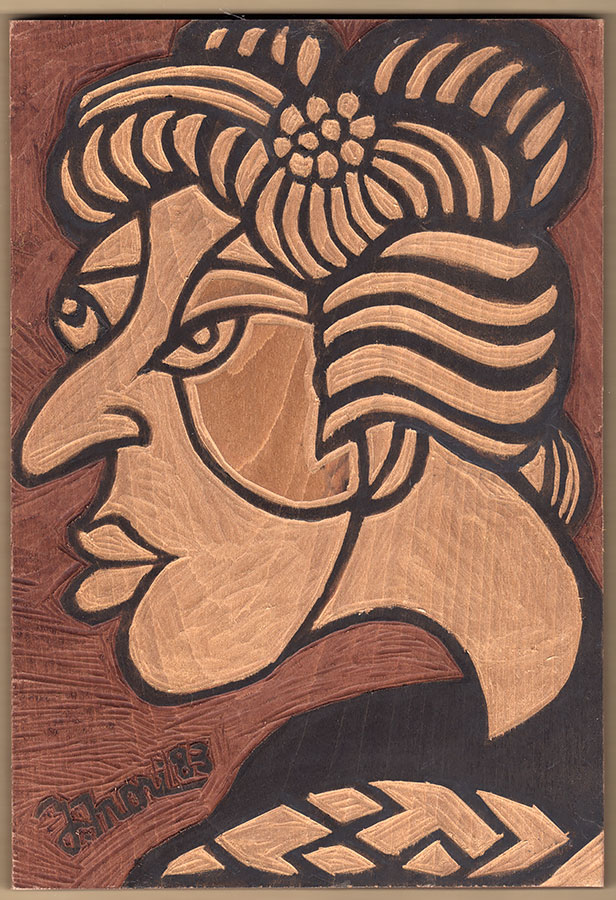

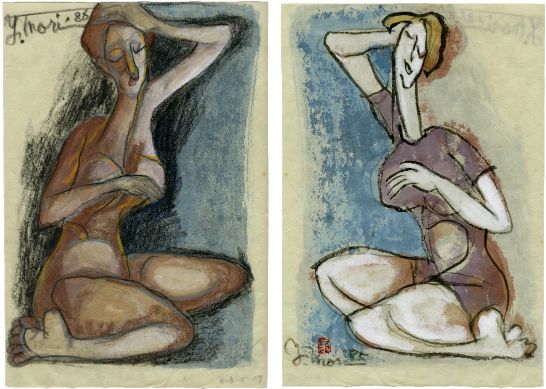

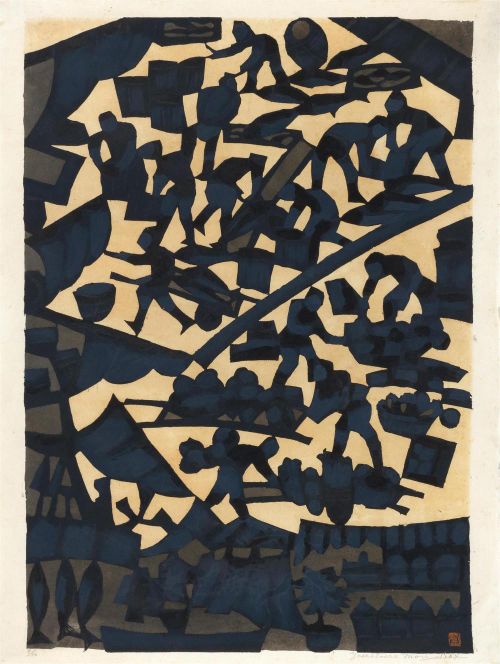

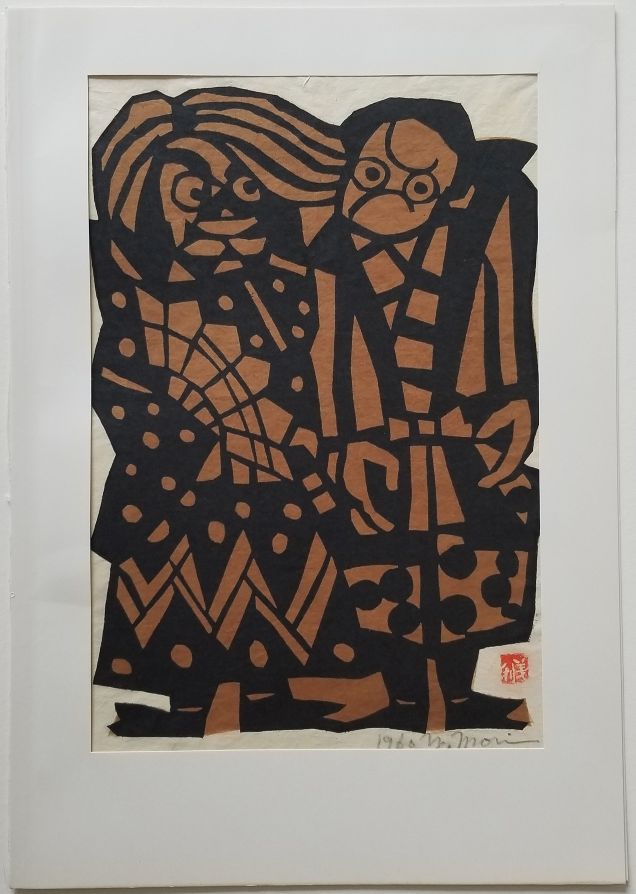

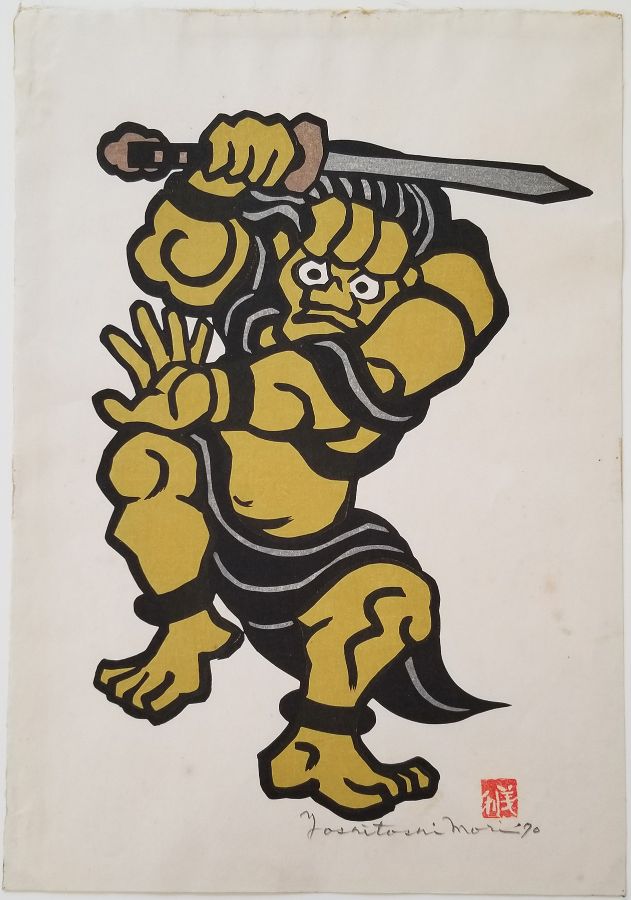

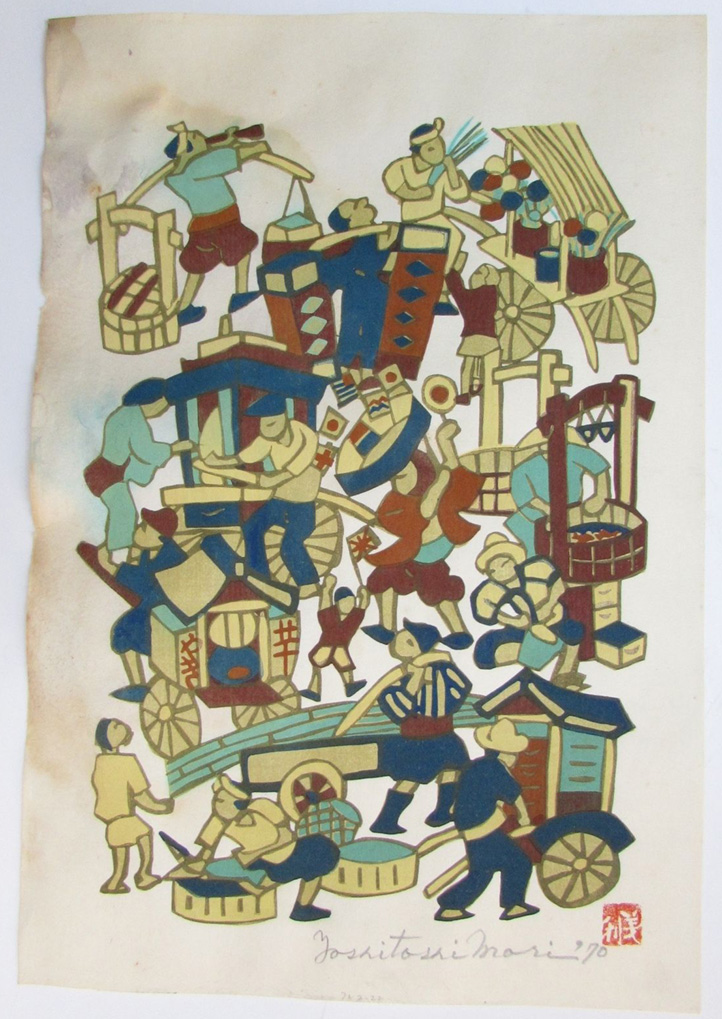

Mori’s work focused on scenes of kabuki, festivals, figures of craftsmen, and characters from traditional Japanese stories. Mori created prints based off of Japanese prose classics The Tale of Genji and The Tale of Heike. In 1973, his series of seven prints depicted artisans in a bold yet simple manner, which celebrated the craftsmen as strong and monumental figures. Mori used large, blocked out impression of various colors. His prints stand out because of his liberal use and mix of color in each print. In Margaret K. Johnson’s and Dale K. Hilton’s book Japanese Prints Today: Tradition with Innovation (published by Shufunotomo Co., Ltd., 1980), “Mori’s art dramatizes not only the subject matter itself, but also the abstract relationships of space, color, and line, which strengthen the total expression.” More signed his prints as “Yoshitoshi Mori,” in Japanese characters, and with a red seal.

The Second World War and Great Tokyo Air Raid halted some of Mori’s business as a textile and kimono dyer. However, art grants revived the arts in Japan after the war and Mori’s business and artistic practice thrived. In 1949, Mori built a home for his wife and three kids in Nohonbashi, Chūōku. The same year, he became a member of the craft section of the Kokugakai (National Picture Association). In between the years 1957 and 1977, Mori displayed his work in over 30 international exhibitions and numerous solo shows. In 1959, his prints Year-end Market 1 and Year-end Market 2 was critically praised at the 1st International Biennale of Prints in Tokyo. James Michener included Mori’s print Kagura no doke (Comic Shrine Dancers) in his 1962 portfolio of prints in the book The Modern Japanese Print: An Appreciation. Mori created hundreds of print designs throughout the 1970s in his late age. The Honolulu Museum of Art held a retrospective of Mori’s work in 1979. He was the first living Japanese artist to receive this honor by the museum. In 1984, Mori was awarded an honorary doctorate by Maryland University.

Yoshitoshi Mori died on May 29, 1992, a few days after the end of his last solo show at Wako Gallery in Tokyo. His work can be found in numerous private collections, such as the official residence of the Prime Minister of Japan, and major museums like the Tokyo Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura Museum of Modern Art, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, Art Institute of Chicago, British Museum, Berlin National Museum, Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, among others.

Japan

Japan