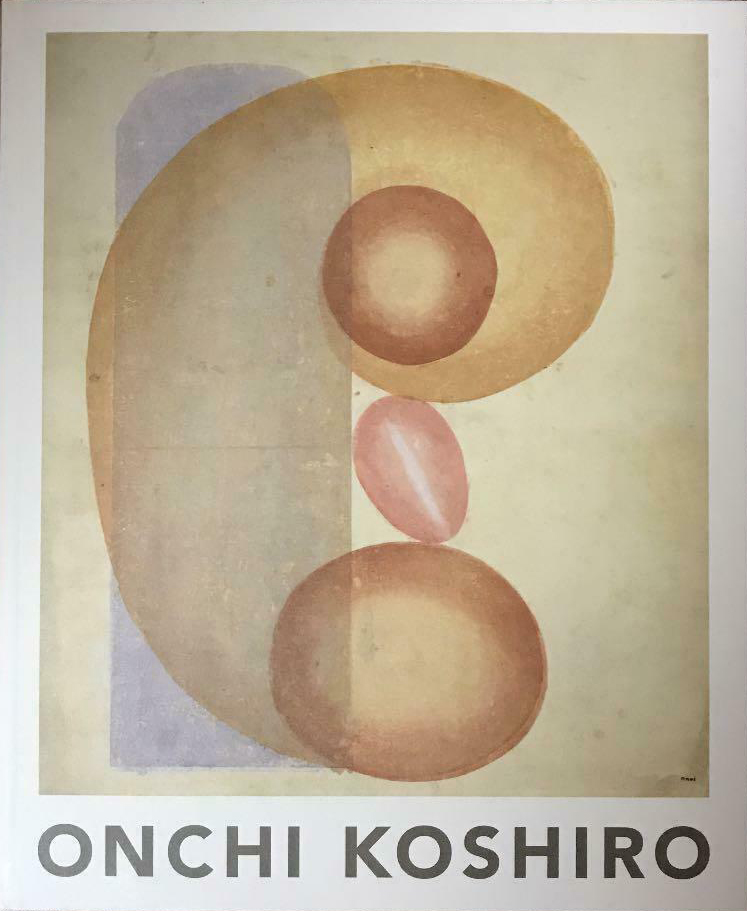

Kōshirō Onchi (恩地 孝四郎, Japan, 1891-1955) was a printmaker and photographer who is considered today as the father of the sōsaku hanga movement. Onchi is also credited to have produced the first abstract print in Japan.

Kōshirō Onchi was born in Tokyo, Japan in 1891. Onchi’s father, Onchi Tetsuo, was an official of the Imperial Court whose role included overseeing the education of the three young princes of the Imperial family. Onchi Tetsuo was also a skilled calligrapher and master of the Chinese language. Kōshirō Onchi's mother was an experienced koto player. Onchi received the equivalent of a royal education because of his father’s role and learned German throughout his schooling. Onchi also studied oil painting at the Aoibashi branch of the school of Hakubakai after failing the examination to enter Daiichi Kotogakko (First High School). Onchi submitted his work to the artist Takehisa Yumeji (1884-1934) after a call to compile a book of print designs known as Yumeji Picture Collection, Spring Volume. Yumeji was impressed with the young artist’s work and encouraged him to attend the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, which Onchi did in 1910. In 1911, however, Onchi withdrew from his courses to work as a book designer with Kawamoto Kamenosuke of Rakuyodo with the aid of Yumeji. In 1912, he was readmitted to the Tokyo School of Fine Arts and graduated two years later.

Onchi kept working in the field of book publishing. In 1913, he created the print and poetry magazine titled Tsukuhae (Moonglow) with classmates Tanaka Kyokichi (1892-1915) and Fujimori Shizuo (1891-1943). In 1916, Onchi and poets Muroo Saisei (1889-1962) and Hagiwara Sakutarō (1886-1942) produced the poetry magazine Kanjo. Onchi contributed both designs and poems for the publication. Onchi collaborated with Tanaka Kyokichi during the artist’s last months as a result of a terminal illness for the book of poems Howling at the Moon (Tsuki ni hoeru), published in 1917. The same year, Onchi produced his first series of prints, Happiness (Kofuku). In 1919, Onchi entered his prints into the first Nihon Sōsaku-Hanga Kyokai exhibition. Later on, 1921 marked Onchi’s new publication of the art magazine Naizai produced in part with artists Otsuki Kenji (dates unknown) and Fujimori Shizuo (1891-1943). Over the years, Onchi contributed prints to numerous other print series like Minato, Kaze, Shi to hanga, Dessan, HANGA, Shiro to kuro, Han geijutsu, and Kitsutsuki.

Onchi established himself as a reputable book producer in Japan. In 1928, Onchi was approached by a newspaper company to create images of the Lindbergh trans-Atlantic flight that were later produced in his book Sensations of Flight (Hiko kanno), published in 1934. For the next ten years, from 1935 to 1944, Onchi edited 103 issues of the monthly magazine Shosō (Window of Writing), a magazine dedicated to showcasing Japanese graphic design. He also self-published his poetry and prose accompanied by his illustrations: Fairy Tale of the Sea (Umi no dowa) in 1932 and A Dairy of Random Thoughts (Zuiso nikki) in 1935. By the end of his career, Onchi had personally designed over 1,000 book designs for publishers. In 1949, Onchi received the first prize in Japan for his excellence in and dedication for book design.

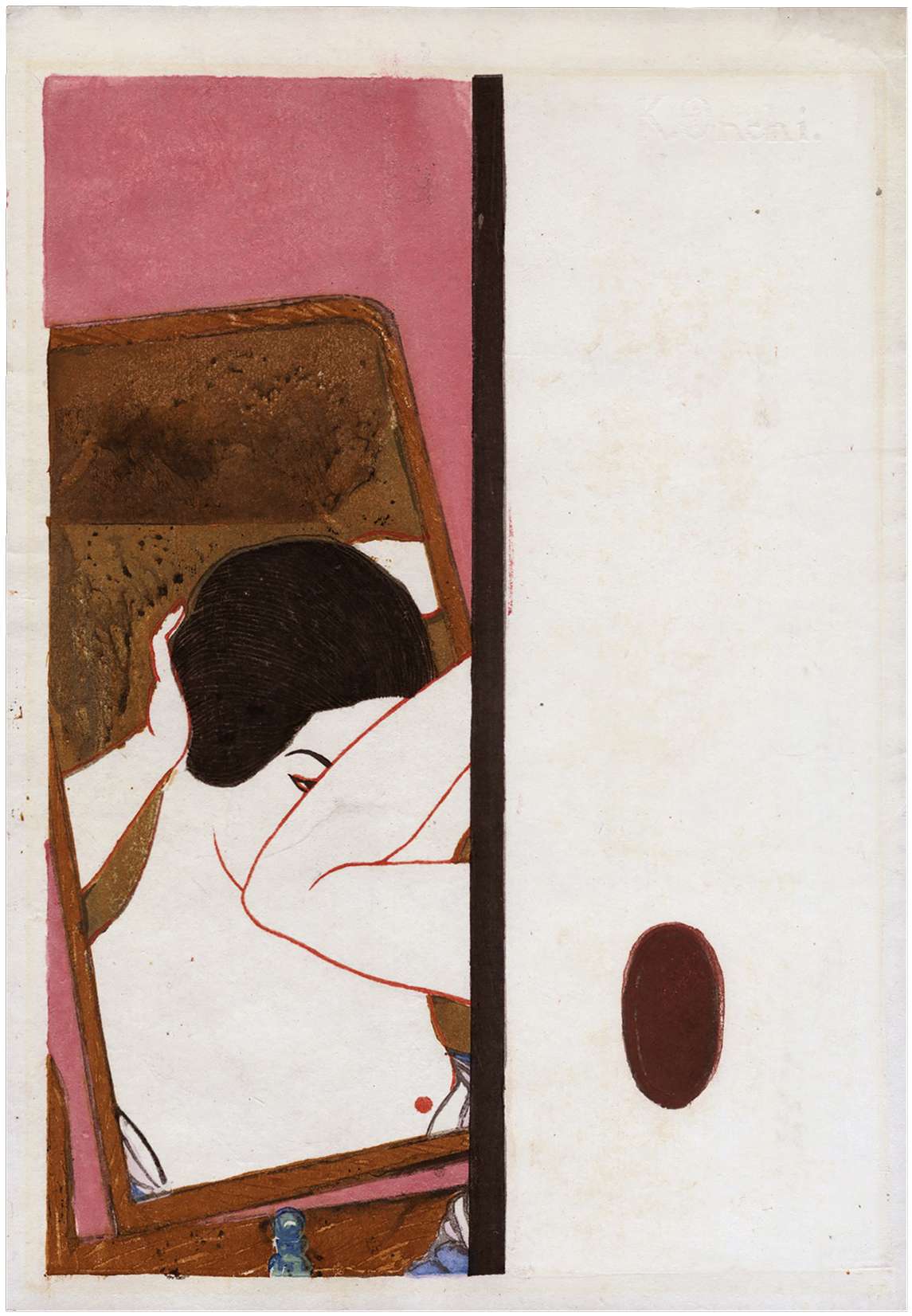

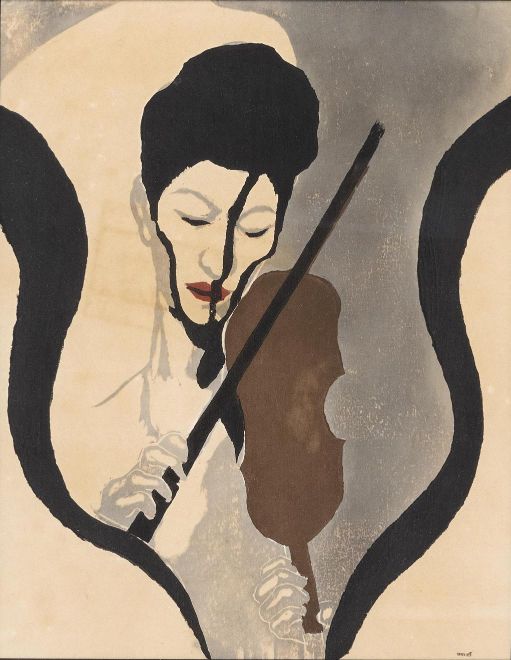

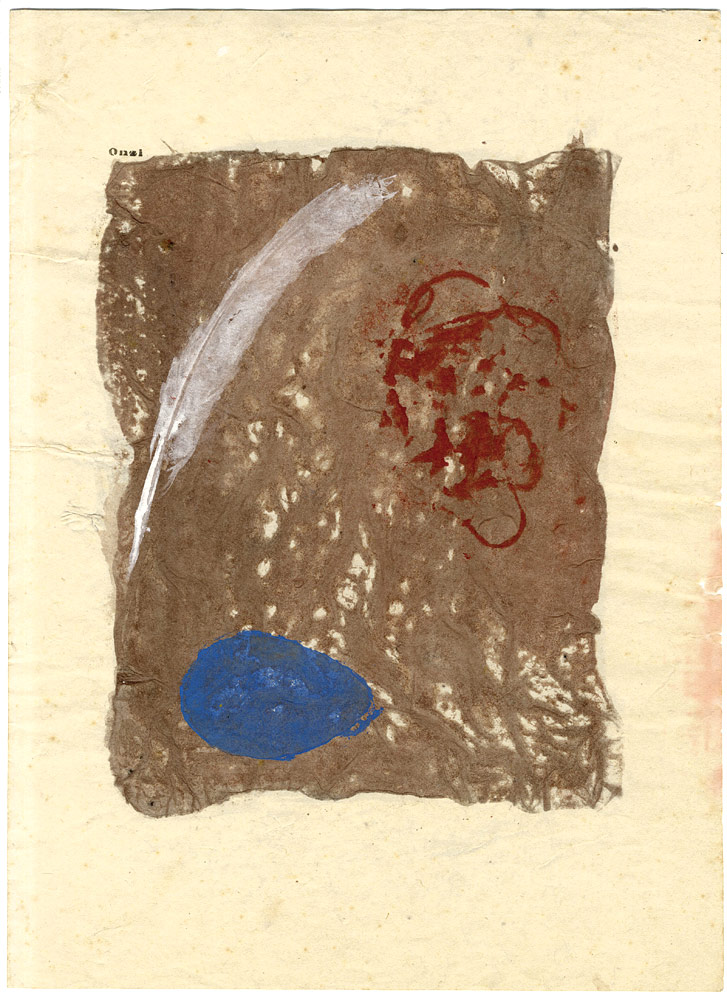

Onchi’s artistic style can be characterized simply as modern and abstract - two styles he believed deeply were the future of art. He also believed printmaking was the most suitable method for expressing modern and abstract art. Onchi’s style can be defined as an expression of his personal eclecticism and emotional spontaneity. Onchi created abstract works by tying symbolic formal elements to various subject matters. Therefore, the descriptive titles of each of Onchi’s prints illustrate his abstract interpretation. He produced a series of prints based on musical notes and lyrics called Lyrique on music compositions, which he was inspired to create after hearing Western Classical artists like Bartok, Borodin, Debussy, Ravel, Scriabin, Stravinsky, and the Japanese classical-style composers Moroi Saburô (1903-1977) and Yamada Kôsaku (1886-1965). His lyric prints are considered the first abstract prints ever created in Japan. As a leader in the sōsaku hanga (creative print) movement, Onchi drew (自画, jiga), carved (自刻, jikoku), and printed (自刷, jizuri) all of his images. The sōsaku hanga movement was motivated by a desire for self-expression and strayed from the traditional ukiyo-e collaborative system where the artist, carver, printer, and publisher engaged in a division of labor. Therefore, the artist took total control of the final image as the initial creator of the design. The artist also assumed the role of director of the prints, not the publishing house. Onchi’s disdain for ujkiyo-e and the practice can be inferred by his expressive techniques he used to apply ink on the paper. Onchi stated that he had no artistic inclination to produce ukiyo-e work and looked to Western painters like Edvard Munch (1863-1944), Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), and Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) as his calling for artistic inspiration. Onchi did look to traditional Japanese calligraphy as intrinsic to the emphasis of control and the use of color, shape, and line in abstract and modern art.

Onchi is considered one of the leading abstract print artists and leaders in the sōsaku hanga movement. Because of his aristocratic status and determined advocacy for art, Japan began to recognize the importance of printmaking and the graphic arts as a fine art. Onchi was a member of the Nihon Hanga Kyokai (Japanese Print Association) and the Nihon Sōsaku Hanga Kyokai (Japanese Creative Print Association). He also exhibited prints in Teiten, a government sponsored exhibition and Kokugakai, the National Painting Association. In 1938, he contributed designs to the print series One Hundred Views of New Japan (Shin Nihon hyakkei). From 1939 to 1945, till the end of the Second World War, Onchi led the Ichimokukai (The First Thursday Society), a monthly group of hanga artists. In 1942, Onchi served momentarily in the Second World War and served as chairman of the Nihon Hanga Hōkōkai (Japanese Public Service Association). After the Second World War, Onchi organized the production of the 1945 print portfolio Scenes of Last Tokyo (Tokyo kaiko zue), to which he contributed 3 prints and wrote the introduction as a gesture to highlight the importance of woodblock printing after the war’s aftermath. Onchi was incredibly active in the arts community after the war and participated in the Kokusai Hanga Kyokai (International Print Association), Nihon Bijutsuka Renmei (League of Japanese Artists), and the Nihon Abusutorakuto Ato Kurabu (Japan Abstract Club). Kōshirō Onchi also had an interest in photography that he developed through the 1930s and 40s. He later exhibited his work in 1951, but focused on printmaking as his chosen medium.

Kōshirō Onchi died on July 3, 1955 at the age of 63 after being hospitalized for complications with his central nervous system. After Onchi’s death, his family permitted memorial editions of his prints to be printed by artist Hirai Kōichi (dates unknown). Onchi’s son Kunio (1920-2001) and printer Yoneda Minoru also reprinted a number of his father’s works posthumously. In 1964, Oliver Statler wrote the introduction for the catalog of Onchi’s work titled Kōshirō Onchi, 1891-1955 Woodcuts, published by the Achenback Foundation for Graphic Arts. In 1975, Keishosha Ltd. published a limited edition book of 170 copies titled Prints of Onchi Kōshirō. In 1986, Elizabeth de Sabato Swinton produced the book The Graphic Art of Onchi Kōshirō – Innovation and Tradition with Garland Publishing, Inc. Additionally, in 2012, Kuwahara Noriko produced the book titled Study of Onchi Kōshirō: Modernity in Japanese Prints, published by Serica Shobō in Tokyo. In 2016, the National Museum of Modern Art held a retrospective and produced a catalog raisonné of Kōshirō Onchi’s work. Kōshirō Onchi’s work is included in numerous collections and major museums worldwide including the British Museum, Art Institute of Chicago, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, and the Honolulu Museum of Art, among others.

Japan

Japan