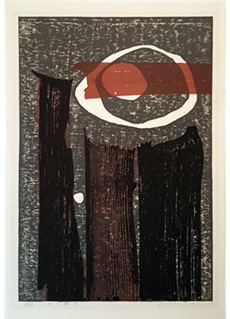

In 1951, printmakers Kiyoshi Saitō 斉藤清 (1907–1997) and Tetsurō Komai 駒井哲郎(1920-1976) were awarded top prizes at the Sao Paolo Biennale, gaining instant recognition for Japanese prints in the increasingly global art world. Their success, unmatched by painters and sculptors at the same biennale, represented a flourishing of Japanese printmaking from the 1950s to the 1970s. The resurgence of creative printmaking in postwar Japan was characterized by innovative, abstract styles and themes that engaged with the rapid transformations of the era. Promoted by artists around the world as the common language of modern art, abstraction was thought to espouse international humanism, individualism, and liberalism following the traumatic experiences under the totalitarian regimes of World War II. This trend toward self-expression and barrier-breaking in the arts ushered in an unprecedented age of experimentation reinforced by transnational networks of avant-garde artists in Japan, Europe and America.

The postwar Japanese avant-garde’s “break” with tradition paralleled their European and American counterparts, though in a distinct cultural context. Japan’s crushing defeat and the subsequent American Occupation (1945-1952) initiated a radical shift in cultural values: Emperor Hirohito (1901-1989) was stripped of his status of deity, the constitution was rewritten entirely, and many high-ranking officials in government and military were on trial for war crimes, all against the backdrop of rapid reconstruction and economic growth. Japan sought to reinvent itself from a defeated nation to a democratic society by surmounting wartime experiences and renegotiating its position in international politics. After the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, the country became a mainstay of the U.S. blockade against Communism, eliciting mass protests to the renewal of the U.S.- Japan Security treaties and Vietnam War throughout the 1960s. Artists’ move towards abstraction and experimentation was inextricably tied to these profound changes in society.

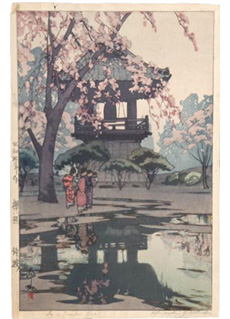

The ethos of the immediate postwar years is epitomized by Jiro Yoshihara (1905-1972) and The Gutai Art Association’s challenge to “Do something that no one has done before!” However, as with painting and other experimental work during this time, abstract printmaking in Japan evolved from a multifaceted dialogue between tradition and modernism. Japan’s history of printmaking began in the 8th century to disseminate Buddhist texts and flourished as a popular art form from the Edo Period (1603-1868) into the late 19th century. In early 20th century Japan, ideologies surrounding printmaking shifted with the Creative Prints, Sōsaku Hanga (創作版画), movement, which evolved in opposition to the New Prints, Shin Hanga (新版画), movement. New Prints maintained greater continuity with the ukiyo-e tradition publishing, subject matter and production processes of the past, where a print was produced by a team of separate specialists: artist, carver, and printer. Departing from this collaborative process, Creative Prints emphasized the individuality and personal expression of the artist with the maxim ‘‘self-designed, self-carved, and self-printed.’’ While printmaking was gradually subsumed into propaganda efforts during the interwar years, a few key figures continued to promote the evolution of creative prints as modern art.

One early proponent and influential leader of Creative Prints movement, Kōshirō Onchi 恩地孝四郎 (1891–1955), identified prints as a key component of Western modernism particularly suited to abstraction. Onchi encouraged the work of abstract print artists during the inter- and immediate postwar years with his First Thursday Society and Modern Print Study Society. Onchi’s status as chairman of the Japanese Public Service Print Association also permitted printmakers in his circle a greater opportunity to experiment during the war and Occupation. American patronage during the Occupation became a key factor in the popularization of abstract subject matter and international dissemination of creative prints. Onchi and Hiroshi Yoshida (1876-1950) often organized printmaking demonstrations for Americans in their homes, and by the mid-1950s there were nearly 300 print artists working in abstract styles. Onchi also hosted American print collectors at the First Thursday Society, including collectors Oliver Statler (1915-2002) and James Michener (1907-1997).By the time Tokyo-based, Canadian expatriate Gaston Petit published his 44 Japanese Print Artists in 1973, it appeared there was an almost exclusive preference for printmakers working in avant-garde, abstract styles. Invigorated by the growing demand and a renewed sense of possibility accompanying postwar reconstruction, many printmakers adopted bold, geometric design that conveyed an exhilarating sense of motion. For example, early prints by Chizuko Yoshida 吉田千鶴子 (1924-2017), such as Jazz (1954) and Sounds in the Night (1953), capture the spontaneity and excitement of aural experience with vivid colors and the repetition of swirling, zig-zagging lines and layers of geometric shapes.

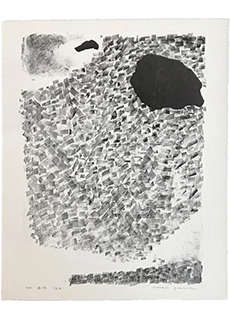

For Onchi and his postwar circle, the print was well suited to conveying the expressive qualities of flattened forms best evinced by early semi-abstract works by Yoshida Hodaka 吉田 穂高 (1926-1995). Woodblock, in particular, enabled a close encounter with medium and material. A number of artists, including Reika Iwami 岩見禮花 (b. 1927), experimented with incorporating the ligneous features of the block into their compositions. Noting that “artistic function in printmaking comes from the creative intention,” Onchi encouraged artists to pursue self-expression and nontraditional techniques. Among them, self-taught printer Haku Maki 白巻 (1924 – 2000) experimented with avant-garde, labor-intensive printmaking process, which involved blocks constructed of cement, woodblock, etching press and sometimes cardboard. Masaji Yoshida 吉田政次 (1917-1971) designed blocks resembling jigsaw puzzles from a single board, which allowed him to raise each piece individually for printing. He also printed to moist, unsized paper, resulting in softer lines and subdued geometric shapes. Yoshida Chizuko also experimented with embossing to add a three dimensional element to her more minimal work such as Start of the Water (1968).

Unprecedented transnational exchange during the postwar period led to a growing sense of internationalism and groundbreaking innovation in the contemporary print world. By the early 20th century, printmaking in Japan had already become increasingly international as artists worked and built reputations in Europe and the Americas. Modernist printmaker and calligrapher Toko Shinoda 篠田 桃紅 (b.1913), for example, moved to New York on Japan Society Fellowship from 1956 to 1958, where she associated with the art dealer Betty Parsons (1900-1982) and was exposed to the work of the Abstract Expressionists. Following in the footsteps of the previous generation of Yoshida family artists, Chizuko and Hodaka Yoshida travelled frequently, using their sojourns to seek inspiration and develop their practices. Exposure to Onchi and other creative print artists’ work also served as the impetus for the printmaking career of Oliver Statler’s translator, Japanese-American artist Ansei Uchima 内間 安瑆 (1921-2000). Uchima’s prints adopt the visual language and improvisational approach of abstract expressionism in conversation with traditional Japanese materials or motifs.

The establishment of the International Print Association in 1953 and the Tokyo Print Biennale in 1957 revitalized exchange between printmakers around the world. Recognition of prints by official art institutions such as the newly founded National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo, moreover, contributed to the integration of printmaking into the wider realm of contemporary art in Japan. Connections between postwar printmaking and painting were particularly strong as many of the avant-garde were trained as oil painters (Iwami, the Yoshidas, Uchima) or calligraphers (Maki, Shinoda). As artists had an unprecedented access to training in international printmaking techniques— etching, intaglio and lithography— many painters began to work across media. Shinoda’s nuanced combination of Japanese calligraphy traditions and expressive lithograph have made her one of the most successful Japanese artists in history. Shinoda often even blurred the lines between media by adding hand-painted elements to her gestural abstract prints. Printmakers also participated in wider multidisciplinary discourse among the avant-garde about the relationship between Japanese tradition and international modernism. Similar to their contemporaries in Euro-America, many Japanese artists also attempted to locate the universal in “primitive” cultures, incorporating Shinto, Buddhist and folk-inspired motifs into their art. In his Poem series, Maki portrayed his personal interpretation of Chinese characters as esoteric hieroglyphs imbued with emotive power. Hiroshi Yoshida, meanwhile, extended appropriations of the past beyond the Japanese archipelago to incorporate motifs from Pre-Columbian civilizations after a trip to Mexico in 1955.

Postwar artistic exchange between Japan, Europe and the United States produced a rich hybridity in which Euro-American modernism influenced the Japanese avant-garde while Japanese calligraphy and Buddhist philosophy influenced the American avant-garde. By invoking the lingua franca of abstraction, Japanese printmakers asserted their internationalism and made significant contributions to the genre of contemporary prints. Drawing from Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, Color Field Abstraction, and Pop- printmakers were perhaps unmatched by other members of the avant-garde in their experimentation, scope and self-expression. The rich complexity of prints by these masters require close-looking as they express a striking individualism and deep artistic response to the rapid transformations of the 1950s and 60s, in dialogue with the past.

Further Reading

Chong, Doryun, et al. Tokyo, 1955-1970: a New Avant-Garde. Museum of Modern Art, 2012.

Monroe, Alexandra and Ming Tiampo, et al. Gutai: Splendid Playground. Guggenheim, 2013.

Smith, Lawrence, ”Japanese Prints 1868–2008” in Perspectives on the Japanese Visual Arts, 1868-2000, edited by J. Thomas Rimer. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, 2012.

Volk, Alicia. Made in Japan: The Postwar Creative Print Movement. Milwaukee, WI & Seattle, WA: Milwaukee Art Museum in association with University of Washington Press, 2005.

Winther-Tamaki, Bert, Art in the Encounter of Nations: Japanese and American Artists in the Early Postwar Years. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, 2001.

Winther-Tamaki, Bert, “The Ligneous Aesthetic of the Postwar Sōsaku Hanga Movement and American Perspectives on the Modern Japanese Culture of Wood,” Archives of Asian Art, Volume 66, Number 2, 2016, pp. 213-238.

Haku Maki

Haku Maki  Kiyoshi Saito

Kiyoshi Saito  Ansei Uchima

Ansei Uchima  Hodaka Yoshida

Hodaka Yoshida  Hiroshi Yoshida

Hiroshi Yoshida  Reika Iwami

Reika Iwami  Chizuko Yoshida

Chizuko Yoshida  Toko Shinoda

Toko Shinoda  Masaji Yoshida

Masaji Yoshida  Koshiro Onchi

Koshiro Onchi