“When you look at [a] print by Yoshitoshi… for a moment that era: that era which you couldn’t tell if it was Edo or Meiji, an era in which night and day seemed to have merged and become one...doesn’t it appear before your eyes so vivid in an instant?”- Akutagawa Ryūnosuke, “The Good Man of the Enlightenment,”1919 (trans. Chelsea Foxwell)

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi 月岡 芳年 (1839–1892) is an undisputed master of woodblock print design whose career spanned the most profound period of transformation and modernization in Japanese history, the Meiji period (1868–1912). Often referred to as the “last ukiyo-e master,” Yoshitoshi is widely recognized today for revitalizing the medium of woodblock prints with ingenious designs that reflected the drastic changes in Japanese society at the time.

Born in Edo (modern-day Tokyo), Yoshitoshi apprenticed under ukiyo-e master Utagawa Kuniyoshi 歌川 國芳 (1798–1861), and published his first woodblock print, Picture of the Heike Clan Sinking and Perishing at Sea (1853), at the age of 14. Despite unsubstantiated speculation about his struggles with mental illness, Yoshitoshi was a prolific artist. He produced thousands of color prints for over 50 publishers, illustrated newspapers and books, and was also a respected painter. His popularity and commercial success are a testament to the uniqueness of his work despite a growing preference for lithography and photography during the Meiji period.

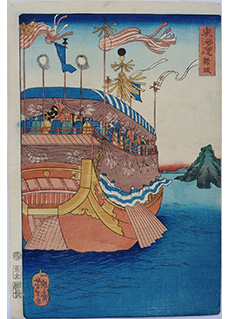

Yoshitoshi had established his own workshop by 1868 when the shogunate military government that ruled Japan during the Edo Period (1600-1868) was overthrown and the emperor was reinstated as the highest governmental authority. He is said to have witnessed the violent battles that restored the emperor to power, inspiring gruesome warrior and battle prints in the style of his teacher, Kuniyoshi. Opening Japan to Westernization and industrialization after 200 years of isolation, the restoration of the Meiji Emperor ushered in a period of rapid, widespread changes to Japanese life almost overnight. Eager to gain parity with the West, Japan rapidly adopted foreign technology, philosophy, literature, fashion and art, overhauled its political systems, and participated in international trade. The Meiji government also sought to elevate the status of its cultural traditions on the global stage by organizing Japan’s first public exhibitions and participating in world’s fairs. Meiji artists responded to this overwhelming influx of information by blending styles and techniques to develop new, modern aesthetics.

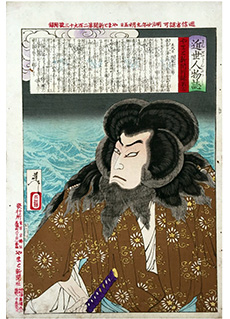

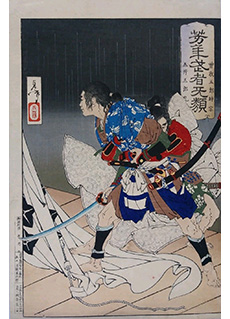

By the 1870s, Yoshitoshi had developed a unique personal style distinctive from other prominent print designers. While many of his contemporaries highlighted (and even satirized) contemporary historical events and transformations, Yoshitoshi made innovative designs of familiar scenes from the canon of Japanese history. He integrated western visual techniques of shading, foreshortening, and perspective with dynamic compositions that frequently suspended viewers in a tense moment of a story and the emotional of his subjects in those moments. These prints resonated with the general public who were experiencing the turbulence and uncertainty of the era firsthand; his work evoked a sense of nostalgia for the past while also expressing real anxieties about the future.

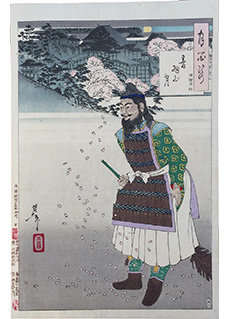

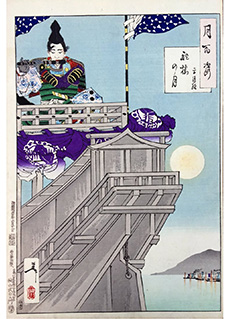

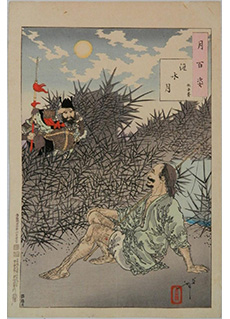

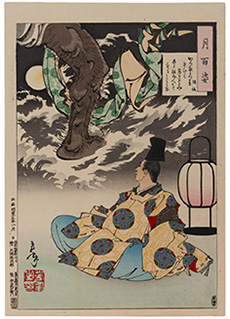

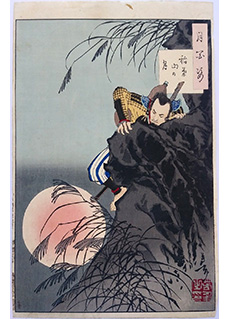

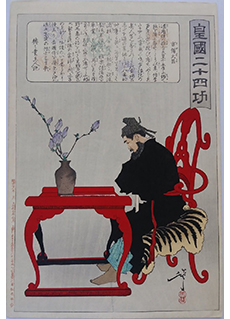

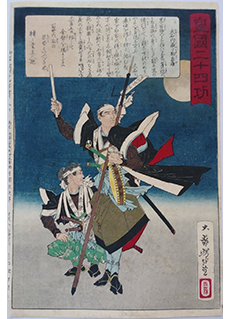

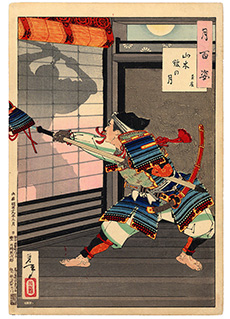

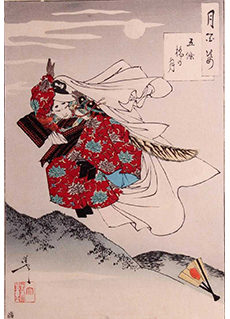

Yoshitoshi’s popularity rose in the 1880s after publishing what are now his most celebrated series, One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (1885–1892) and Thirty-two Aspects of Customs and Manners (1888). One Hundred Aspects of the Moon was so iconic that its completion was announced in the newspapers and collectors waited in line outside the publishers to purchase copies. The series consists of one-hundred images, each referencing different stories from Japanese and Chinese history, legend, and folklore that feature the moon. It also incorporated the central print from Yoshitoshi’s most famous print triptych, Fujiwara Yasumasa Plays the Flute by Moonlight (1883), which was in turn based on his scroll painting of the same title. These works captured the imagination of international audiences with Yoshitoshi’s distinctive combinations of western perspective, dynamic, diagonal compositions and often subdued color palettes. The innovative compositional elements came together to portray the emotions of each subject during a crucial but fleeting moment in their story, further underscored by the ever changing presence of the moon.

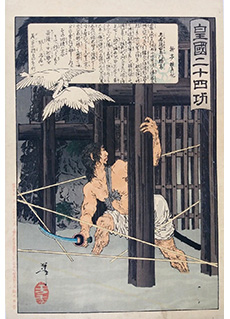

Inaba Mountain Moon (1885), for example, shows the first Shogun, Toyotomi Hideyoshi 豐臣 秀吉(1537–1598), scaling a cliff to Gifu castle by the light of a large full moon. He is seeking an unguarded route into the Saito stronghold of Gifu castle. Rather than depicting the heat of the siege, Yoshitoshi captivates the audience with a quiet moment of determination and focus, communicated in the warrior’s facial expression as he pulls himself up the jagged cliff face.

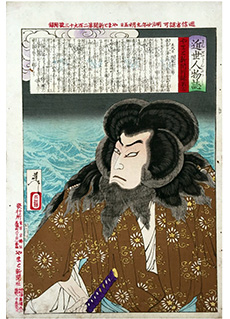

Meanwhile, viewers familiar with the story of Tsunenobu (1886) would have been able to identify with Heian court official Minamoto no Tsunenobu’s 源経信 (1016-1097 AD) shock as he recites a poem to the sound of a beating cloth in the night and is answered by a giant sky demon with lines from another poem! Following Tsunenobu’s gaze to the upper left corner of the sky above the moon, Yoshitoshi provides viewers with the very instant the demon’s massive, hairy foot descends upon the clouds.

Other prints in the series do not portray a particular scene from literature or history but instead celebrate Japanese rituals and traditions reinstituted and preserved during the Meiji period. For example, Dawn Moon of the Shinto Rites (1886) shows a Japanese Shintō festival celebration for the god Sannō (the mountain king). A dancer in the costume of the mountain king rises sharply above the viewer as if viewing the procession from street level. Vibrant colors and meticulous details on the fabrics and festival floats alert observers to the opulence and splendour of the event. A small rooster on the top of a temple drum also symbolizes an era of auspicious rule.

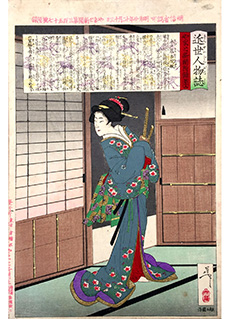

Yoshitoshi’s series Thirty-two Aspects of Customs and Manners represents a different side to his novel style and impact on future generations of Japanese printmaking. Thirty-two Aspects of Customs and Manners consisted of images of beautiful women (bijin-ga) in various settings. The series was unprecedented in its representation of women from across Japanese history and social class, including portraits of court ladies, housewives, business women, servants, courtesans and prostitutes as well as its more realistic renderings of the women’s facial expressions and figures in three-quarter view. With sensuous attention to fashion of modern women emphasized by newly available aniline dyes, Yoshitoshi’s various beauties, such as the woman in Wanting to Go Abroad (1877–78), anticipate the intimate compositions his successors would create of stylish women during the New Prints (shin-hanga) Movement in early 20th c. Japan.

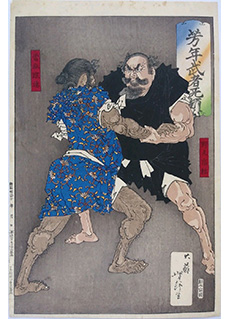

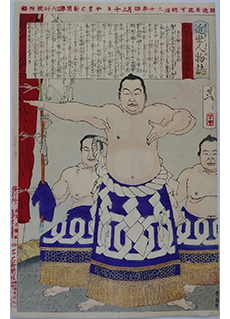

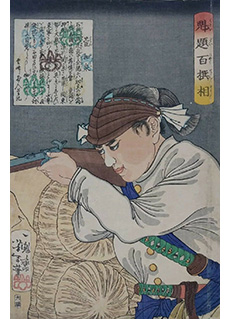

Although his woodblock prints are now regarded and collected as high art, Yoshitoshi’s legacy as a popular artist continues to be celebrated today in contemporary tattoo culture. While tattoos have remained relatively taboo throughout most of Japanese history, decorative tattooing (irezumi) blossomed among the popular culture of the Yoshiwara pleasure districts and working class during the Edo period. Tattoo designs often evolved alongside woodblock prints and Kabuki theater plays. Yoshitoshi was well known for showcasing the beauty of tattoo motifs of his time in many of his prints, especially those featuring kabuki actors and the series Strong Heroes of the Water Margin (1868). His particularly imaginative, detailed renderings of tattoos in many of his works provide fascinating records of Japanese tattoo culture that continues to mesmerize woodblock print and tattoo aficionados alike. A number of his prints even take up the process of tattooing as subject matter. A scene from Thirty-two Aspects of Customs and Manners (1888), for example, shows a young courtesan receiving a tattoo with the character for love, likely the beginning of a tattoo for her lover.

Yoshitoshi’s designs for scenes from Tales of the Water Margin (Suikoden), a 14th c. Chinese epic popular in Japan, showcase incredibly meticulous tattoos on the bulging muscles of heroic renegades who battled on behalf of the poor and oppressed. In late Edo, these ukiyo-e inspired compositions from Tales of the Water Margin were sometimes employed as subversive symbolism for the tattoos of vigilantes who rebelled against the authority of the shogunate. This subject matter still resonates with contemporary tattoo artists today and is referenced in their work. Los Angeles-based Christopher D. Brand’s tattoo series,108 Artists of Los Angeles, for example, interweaves iconography from Tales of the Water Margin with 1980's Los Angeles Chicano history and tattoo culture. (The profound influence of ukiyo-e on tattoos and their interconnected history was recently explored in the exhibition Perseverance: Japanese Tattoo Tradition in a Modern World (2014), organized by the Japanese American National Museum.)

In addition to tattoos, the influence of Yoshitoshi’s innovative designs continue to reverberate across contemporary art, illustration and design. The artist’s striking ability to recast Japan’s past through a modern lens enabled him to redefine the woodblock print in a progressively global world. His seamless integration of western and Japanese techniques, merging past and present, make his compositions feel thoroughly modern and continually provide inspiration to all who encounter his work.

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi